Contact Me

Most Recent Blog Posts

05/16/2024

ChatGPT and the Educational Pump Fake

05/25/2023

On Failure...

05/16/2023

An Ode to the GOAT (of Failure)

02/12/2021

Failure Judo: Take Time to Recover

07/31/2020

Failure Judo: Build Community

07/30/2020

Failure Judo: Discuss

07/29/2020

Failure Judo: Be Meta

07/28/2020

Failure Judo: Tinker

07/27/2020

Failure Judo: Practice

07/26/2020

Failure Judo: Reframe the Experience

07/25/2020

Failure Judo: Manage Loss

07/24/2020

Failure Judo: Take Incremental Steps

07/23/2020

Failure Judo: Fail on Furpose

07/22/2020

Failure Judo: Visualize Failure

07/21/2020

Failure Judo: 11 Tools to Make Failure Work for You.

07/20/2020

Perseverance Isn’t Enough.

02/05/2020

Why You Should Try New Things

01/09/2020

Piaget and Failure…

01/04/2020

The Value of Struggle

01/02/2020

The Fear of Failure

11/16/2019

Why Failure Beats Practice Alone

11/14/2019

Reclaiming Failure Tactic: Visualization

11/05/2019

Legos, the Process, and Failure

10/30/2019

Fail First, Succeed Later

10/25/2019

Failure... Like Riding a Bike

10/24/2019

Michael Jordan: Faiure

10/23/2019

Pole Vaulting - A Journey of Failure

10/18/2019

Some Big Questions About Assessment

05/16/2024

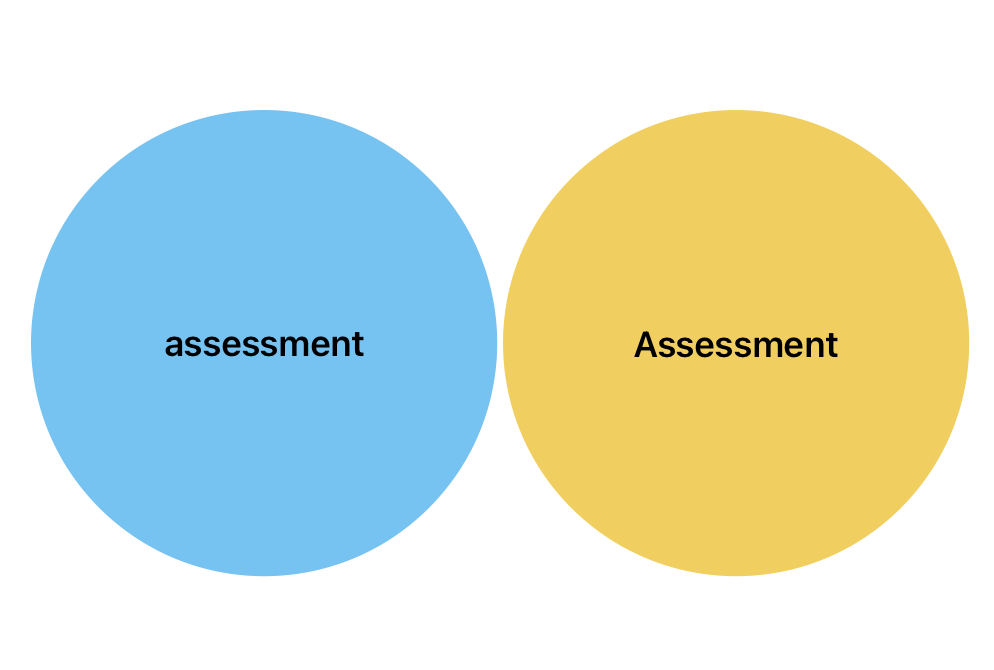

Assessment (uppercase A) in higher education is an interesting animal. In particular, I am thinking about the evolution and the role of Assessment in the California Community Colleges, where I have spent my career teaching and leading. To be clear, Assessment is the formal act of measuring student performance on Student Learning Outcomes (SLOs) and reporting them in some kind of formal way. This is work that is required by the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior College, which is the accrediting body for 115 of the 116 public community colleges in California. When I say assessment (lowercase a), I mean the aspect of teaching where, in the most authentic way possible, we ask “Did the student learn the thing that they were supposed to learn?” I’ll go ahead and say the thing that you might be thinking right now - Shouldn’t those be the same thing, or at least have significant overlap? Of course, the answer is yes, and I can tell you that culturally and practically the broad answer seems to be "no".

The Venn diagram of Assessment with assessment in many classes might even show two separate circles, reflective of the idea that one might teach their class, assessing the levels of student knowledge relative to the material they cover, and then at times they also "Do Assessment", measuring and reporting SLO performance using some other measure.

So I have some questions…

If what we teach and assess doesn't lend itself to SLO Assessment, then how do we explain the difference?

SLOs are intended to be the core representation of what we have in the curriculum, right? As in, after a student finishes this class, these are the big things they will have mastered. In my mind, SLOs should adequately cover the scope of the course, and everything taught in the course should in some way be connected to an SLO. If that's overreach on my part, then what percentage of the course can be unrelated to SLOs, and how do we come to that?

While I'm on the topic - What is the relationship between grades and assessment? It feels like there should be a very strong correlation between good grades, and good SLO performance. I wonder how many courses are out there, where it is mathematically possible to Fail the course, but succeed in the SLO assessment, or the other way around. If we consider extra credit, then how does that figure in? Does that strengthen or weaken this correlation?

Here's a really interesting line from ACCJC's standards: The institution awards course credit, degrees and certificates based on student attainment of learning outcomes. (Standard A.9)

Wait a minute. Based on SLO attainment? What about GRADES? SLO attainment doesn't even show up on the student transcript. It is my understanding that many faculty and schools don't even report individual SLO attainment for each student. So, I have another question: If you don't assess every SLO, for every student, for every section, every semester, then HOW IS IT POSSIBLE to award anything based on SLO attainment? I don't see how it is.

ACCJC's standards also require that "In every class section students receive a course syllabus that includes learning outcomes from the institution’s officially approved course outline." (Standard A.3). I think it's great that we do this - telling students about the big things they will learn on the class allows them to see where they are going. It would be even better if the students could see how these SLOs fit into the overall program SLOs, but that might be a lot to ask for now. So, it makes me wonder – How many students hear about SLOs after they read them on a syllabus? Or, if I can be really abrasive, is there any real value to putting SLOs on the syllabus if the students never hear how they did on them? I know, I know. That would require individual Assessment for every SLO/student/section/term and an effective way to communicate that to students. Oddly, the tools seem to exist, but the practice and culture do not (in a significant or nearly universal way).

All of these questions beg the bigger question: Why are we doing Assessment? What is the point of doing this, when grades have served the purpose of telling students how they did for so long?

Based on my limited experience, it seems that grades, in fact, have NOT served their purpose effectively. However, since grades are deeply engrained in our culture ("Hey Ron, nice job on that marketing presentation – A+ work.") and our systems (as the terrible spouse of the worse-than-worthless Carnegie Unit). I believe that it was the recognition that grades are ineffective that spawned Assessment in the first place.

At best, the advent of Assessment was the start of an important conversation. At worst, it was the layering of a new ineffective system on top of an existing ineffective system. The end result is a weird, academic rendition of dueling banjos.

Wow, I sure did a great job pointing out all the problems, didn't I? Now what?

How do we go from dueling banjos to a way of thinking and teaching where Assessment and assessment are the same thing? Where we and students know the big things that they need to learn, and where our teaching is focused around developing authentic understanding of what is learned?

That's a worthy discussion to have. I think there are many, many folks out there who have something to contribute to it, and I believe it can be done – it's just going to require some brave steps and some big shifts in how we think about this thing called "education". I'll leave you with one more big question:

What does it look like when Assessment and assessment converge in a meaningful way?

ChatGPT and the Educational Pump Fake

05/25/2023

I love a good pump fake in basketball. It’s one of those moves that when done properly, leaves the victim looking like a helpless child who is trying to play a game with grown-ups. The pump fake is one of those rare classic moves that just seems to improve over time, while at its core really staying the same as it always was. For the uninitiated, the pump fake is a feat of athletic slight of hand, where the ball carrier makes the other player, or the victim, believe that they are about to go in a specific direction, or possibly send the ball in a specific direction. This misdirection is often done using the head or the ball (other names: head fake, or ball fake). As humans who are socialized, we are conditioned to expect that where the fake leads, the body will follow, and this is often true… Except in the rare cases where an athlete has specifically learned to move the ball, head or another body part one way without the intent to move anything else in that direction. Pump fakes are effective, because they play upon our conditioning and our expectations to throw us off balance. The best pump fakes usually end up with the victim flat on the floor, out of the game for that critical moment. To watch a master, check out the video below:

Innovation and scientific or technological progress have given many pump fakes to education. The script, played out over and over, usually goes something like this:

Innovator: “Look, I have made a new thing!”

Educator 1: “This new thing will fundamentally change education forever!”

Educators all together: “Three cheers for the new thing!”

Students: <shrug>

Educator 2: “Students will use it to cheat!”

Educators all together: “Ban it from schools!”

Students: <rolling eyes>

Over and over, throughout history, we have seen this script play out. Radio, television, the laser disc player, VCR and portable video camera, and more recently the internet, virtual reality and the cell phone. Educational technology is a virtual parade of pump fakes, not because these ideas have not merit, danger or educational value, but because the learning community at large continuously fails to contextualize their value within a system of learning that places a higher value on what matters in teaching and learning. Namely, providing a social environment where students can build knowledge in ways that make sense to them, and share that learning in authentic meaningful ways. That kind of learning environment can't be ruined, replicated or perfected by AI, or any other technology.

That isn't to say that AI doesn't have tremendous value in education – it does, and we should learn how to harness it and also put it into the hands of students whenever possible, so we can see all the great things they do with it. It's just that if you are dreaming about scaling education using AI-powered instructor bots, or afraid that every assignment will be fodder for ChatGPT, I'm afraid you will be both disappointed and relieved. So how so we keep our focus in the right place?

First, we should work to frame student learning as a change in student thinking that results from a guided experience, rather than the transfer of information and subsequent proof of that transfer. In the right learning framework, we pull AI away from the fringe as savior and destroyer of education and into the range of just another tool we can use.

Here are just a few other thoughts on ways that we might leverage AI in productive ways:

- Better understanding the massive data stream that we produce in LMS and other online systems, to provide us insights into the nuance of successful student behavior, and then iterating on that data to build systems that provide adaptive guidance to students, assisting with engagement and interaction with course materials and activities.

- Ask ourselves questions like, “What if AI was as welcome in my class as pencil and paper? What does a meaningful, AI-inclusive learning environment look like? If I'm preparing a student to work, live and create in the future, how can I serve them well in a world where AI is everywhere?"

- As educators, we should all spend plenty of time with AI, so we know what it is, how it works, and what it can and cannot do.

- When we think about the strengths of AI, we might ask ourselves about the things that we do in education (other than teaching an learning) that could be outsourced to AI to save us time and money, and the free up resources for the things that AI simply cannot do. Things like large, complex pattern recognition, the generation of resources, the retelling or reshaping narratives, evaluation of resources, and many others fall into this group.

- We should be thinking about the ways that AI systems can help us understand our own thinking and behavior. Students should understand these large data models as a means of sharpening their own thinking.

There are so many ways we can use this resource, if we just calm down, take our finger off the panic button, and spend a little time exercising our own creativity. Here's an opportunity for us all to mindfully avoid another pump fake, and keep ourselves in the game.

On Failure...

05/16/2023

My life is full of failures.

I’ve failed tests. I’ve failed people — some of whom are very important to me and who were greatly affected by my failures. I’ve failed several million times to do something just the way I envisioned it in my mind, whether that was drawing a picture, executing a skateboard trick, or remembering to take the trash cans down to the street on trash day. An entire series of books could be written about my many failures as a parent of seven kids. Volume one of the series might be titles something like, “All the ways Bill sucks at caring for babies.” Volume ten, still a work in progress, is tentatively called, “Parenting Adult Children: Discovering the Right Way by Trying All the Wrong Ones First.” Sometimes it feels like the number of failed ideas I’ve had in my life must outnumber the total number of ideas the average person has in theirs. One early tragedy in this pile of failed ideas was my great idea to build, manufacture, and sell actual working hoverboards after seeing Back to the Future 2 in theaters. I’ve failed at work. I’ve failed at home. I’ve failed in the commute from home to work (do NOT ask my wife whether I am a safe driver).

But AM I a failure?

I think most people would look at my life and say, “Absolutely not.” I have a Masters Degree and a Ph.D. from reputable institutions. I’ve had a very long career in Education, where I’ve accomplished some things that made a positive difference for students, and I’ve touched a number of student lives on a personal level. I have a great marriage to a wife that is clearly out of my league in pretty much every way imaginable (brownie points!), a large multiracial family where all seven of my kids genuinely love and support each other. Despite growing up mostly without a dad, I seem to be doing a pretty good job at parenting. My kids, in spite of having many of their own obstacles to overcome, seem to be thriving and finding their way in life — My oldest two decided to pursue college swimming, and both are swimming Division I on full rides, and both are working toward Olympic Trials qualifying times for 2020. The remaining five are each pursuing things that are important to them, but most importantly, they are good people. I think most people would look at my life, and say that I’m doing pretty well — decidedly not a failure.

So, to summarize — Despite my apparent aptitude for failure, and the massive body of evidence that supports my greatness in this category, I’m doing ok. Maybe even better than ok. Someone who knows me might say, “Well, Bill — You’re just lucky you married well.” This is true. My wife has made a massive difference in my life. However, there is something else there. If you look at my failures alongside my successes in life, you will notice a pattern, almost like an echo of one following the other. Where you see multiple failures, you often also see a success. This, I believe, is attributable to the fact that failure is a necessary ingredient in life’s most significant successes. In my life, I have managed to embrace failure as a_ part of the process. Failing isn’t a bad result. It isn’t some kind of endpoint, or a sign that I should quit trying. Instead, failure is a small step on the way to my goals – an opportunity to learn, to improve, and to rise. You see, failure is going to happen in our lives, but our relationship to failure and how we see it, use it, and own it can have a massive effect on our life’s trajectory.

Our relationship with failure can make us better teachers, better parents and better leaders too. When we look at failure differently, it gives those around us the same superpower to reframe their failures into learning opportunities, to excel in the very moment when they lose. It makes our families, classrooms, and organizations more resilient, but also braver and more creative. If we don’t fear failure, two things happen. First, we fail more, but that’s not a bad thing, remember? The second thing that happens is that we become more open, more brave, and more creative. We become better problem-solvers and more tolerant of others’ mistakes. The baggage of failure can be heavy if we let it. It weighs everybody down.

My hope for you, reader, is that you will begin to see failure in a different light. I hope that you will begin to reframe failure, to master it and use it to your advantage, and even embrace it as an ally in your own life.

An Ode to the GOAT (of Failure)

02/12/2021

I’m a 45 year old guy from California. Being born in 1975, and growing up through the 80’s, I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t a fan of the skateboarding GOAT, Tony Hawk. He was born in 1968, so while I literally grew up (and now, am growing old) watching him skate, he was always close enough to my age that he felt like a quasi-peer — sort of like a cool older brother that I never met in person. When I was young, I was awestruck by his skating ability, his innovation, and if I’m honest, how incredibly cool he was. Everyone I knew rode his board, copied his haircut, and had a closet full of Tony Hawk shirts. Now, at my age, I can say that I still watch Mr. Hawk with huge admiration — but of a different sort.

Now that I’m a middle-aged parent of 7 kids, and the son that I used to take to the skatepark is 21 years old and in grad school, I see Tony Hawk with a different kind of respect. Sure, I am still awestruck by his ability to skate at 52, which at 45 I only fantasize about. But I see the kind of person he seems to be, and I’m equally impressed with how he lives his life. I’ve never met him, but I earnestly hope he is really this person:

He pushes himself.

Recently, I saw a video that Tony posted to Twitter, in which he shows himself attempting to land a 720 on his private halfpipe. The tweet, in which he refers to the process as a battle, is great to watch. The <2 minute journey from frustration and likely physical pain to absolute stoke is worth the watch.

His words hit me in an interesting way — “I’m really old. I can’t say for certain that this is the last one I’ll ever do, but can’t imagine doing many more…” But here he is — doing it anyway. A guy that doesn’t need to prove anything to anybody about skateboarding, out here fighting his age and proving it to himself. An easy web search finds a video of the last time Tony was caught on video landing a 900 — the trick that he landed in competition before anyone else — at the very young age of 48.

The trick was first done by him in 1999 at X Games 5 in San Francisco.

As I fight against aging in my own, less impressive way, I find this chronology of degrees-of-rotation-per-year both fun and inspirational. I hope that when I’m 75, he’s still riding (even if in a straighter line).

We too-often make the mistake of equating pushing ourselves with numerical growth or progression. As Tony Hawk shows it, pushing ourselves can simply mean we are trying to do better, or be better than what we would comfortably be otherwise. And that is awesome.

He does good.

Far be it from me to guess what’s in the head or heart of someone I don’t really know, except through the tiny window of social media. But the fact is, Tony Hawk does good. His foundation, The Skatepark Project, has invested more than 10 million dollars into the construction of 637 (and counting) skateparks, that see over six million visitors every year. That’s a lot of kids (and adults) who now have a place to go, where they can engage in a healthy, supportive community. I’ve follower a charity called Skateistan (www.skateistan.org) that works with kids through skateboarding and education in Afghanistan, Cambodia and South Africa for some time. This is a cause that’s very close to my heart, and they use these two powerful tools to make a difference for populations for whom “fun” and “learning” might not be common words. Hawk and The Skatepark Project are there, too.

It’s not just big philanthropy, though. Hawk is known to stash signed boards and gear in places all over the globe, giving out hints to fans. Today, I saw a video of him just driving around in a car, telling kids to “Do a Kickflip!”, and then giving them free swag if they play along. The best part of the video is him cheering them on, and getting excited about people doing a basic trick. As he drives between spots, he reflects on how amazing it is that so many people can do this trick, which in his day meant you were on your way to the pros. Either he’s a great actor, or he actually enjoys encouraging people in the sport in the most basic ways. I won’t even get into the long list of great athletes he’s mentored over the years.

He leans in to failure, and lets the world watch.

Anyone who follows my writing and blog will know that I hold skateboarding up as one of the shining examples of learning through failure. It’s easy to watch someone like Hawk, on some highlight reel, nailing trick after perfect trick, sailing through the air like he was born there, and believe that the experience of skateboarding is just like that for the chosen few who just know how to do it. This concept couldn’t be farther from the truth. I couldn’t find a comprehensive list of his injuries, but I bet that Hawk has regenerated enough body parts in his life to make at least one clone of himself — including a few recently dislocated fingers, according to the video above. And this doesn’t include the millions of times he’s been able to bail safely (think of a sort of controlled fall, where you don’t finish the trick, but you also don’t get injured).

The point is, in skateboarding, you quickly learn that in order to grow and improve, you have to be willing to fail – like, a lot. The better the skateboarder, the more they have leaned in to these failures, embracing the iterative process of learning that leads to success. We know that Tony Hawk has embraced failure, because he’s so great. We also know that he has embraced failure, because he’s always been very open about the process. When he’s trying to learn something new, it’s common for him to post a video – not just showing the finished product, but of the frustrating, often painful journey of trying to get there. This openness normalizes the process of learning through failure, reminding that even the best of the best have to struggle to get there.

He has “positive fight”

Jim Loehr, author of several books, including The New Toughness Training for Sports, frequently uses the term “positive fight” in his list of positive attributes that mentally tough athletes (although I believe the term has a much broader relevance). I think Tony Hawk models positive fight incredibly well in his work, and in the parts of his life that he makes public. When I think of positive fight, my mental image is someone whose body language signals strain, work, and an aggressive pursuit of a goal, but as the camera pans to their face there is a look of genuine joy and a gleam in their eye.

Watching Tony Hawk skate, whether it’s grainy video of him in his teens, or YouTube reels of him asserting dominance over his age in 2021, shows us what positive fight is all about. It’s a reminder that loving what you do isn’t about an easy life, but rather bringing intense, joy-fueled work to something that is important to you. We fail, we get up and try again, and eventually we grow and learn. If we’re willing to do this, to bring our positive fight and willingness to fail, to help others along the way, then I think we can all achieve some level of greatness.